Understanding the impact of urbanization on the wetlands of Yamuna floodplains in Delhi-NCR

-

Wetland values, status and trends

Wetlands play a vital role in providing an array of direct and indirect ecosystem services. Yet they continue to degrade. Urbanization and the associated land use changes have been identified as the primary driver behind wetland loss and degradation. Over the past 100 years, it has been estimated that India has lost 50% of its wetlands1. The wetlands along the floodplain of river Yamuna are no exception. Deforestation, land conversion and developmental activities along the river have resulted in reduced flow, habitat loss and loss of biodiversity. National Capital Region (NCR) is said to be the major contributor to this sad state of the river and its floodplain area.

Delhi-NCR has witnessed a rapid urban expansion in past few decades. From 1991 to 2011, the geographic size of Delhi has almost doubled and similar urban growth has been experienced by the neighbouring cities like Faridabad, Ghaziabad, Noida, and Gurgaon2. A study in the year 2011 revealed that out of 629 wetlands mapped in NCR-Delhi region, 232 (36.9%) wetlands cannot be revived on account of large-scale encroachment3

In this study, the impacts of urbanisation on five wetlands along the Yamuna floodplains in NCR-Delhi was assessed. Wetlands having an area of over 10 ha were selected, these included; (i). Sanjay Lake, Delhi (ii). Okhla Bird Sanctuary, Gautam Buddh Nagar (iii). Jogabai Wetland, Delhi (iv). Peer Baba Wetland, Faridabad (v). Latifpur Bhangar Wetland, Gautam Buddh Nagar.

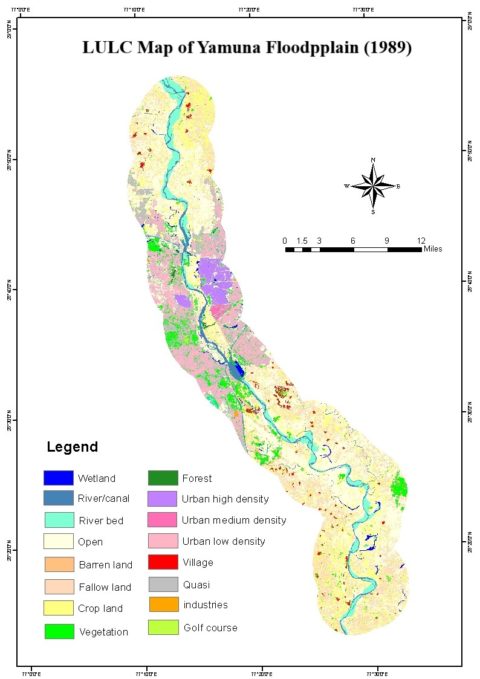

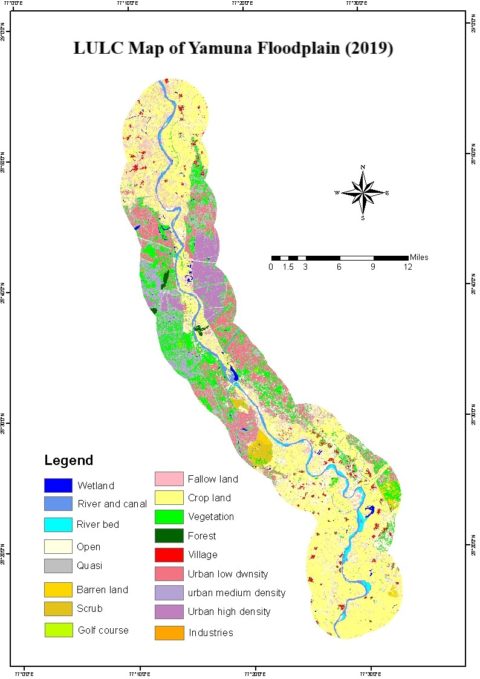

The assessment was based on two attributes i.e. landscape variables and biotic structure. Land Use Land Cover (LULC) maps were developed using remote sensing and GIS tools to understand the change in landscape over a period of three decades (1989 to 2019) while macrophytes were used as a biological indicator to evaluate the wetland health. The temporal analysis of LULC pattern showed an increase in human modified features like cropland (164 acres in 1989 to 303 acres in 2019 – 1.8 times increase) and built-up area (166 acres in 1989 to 284 acres in 2019 – 54.48% increase) and a subsequent decrease in natural areas such as wetlands, rivers and the floodplain. A staggering reduction in wetland area by 46.90% was observed over the three decades.

Macrophytes were good indicators of wetland health. As anticipated, wetlands experiencing disturbances in the form of discharge of sewage, garbage dumping and other non-point sources of water pollution had higher ratio of invasive species cover to native cover and a lower ratio of open water to vegetation cover as compared to wetlands experiencing low and moderate levels of disturbance. Another interesting finding was the influence of wetland from the road on the extent of invasive species. Since roads serve as dispersal routes and facilitate the establishment of alien species, wetlands closer to well established roads had higher cover of invasive species.

Temporal analysis of LULC pattern over a period of three decades (1989 to 2019) showed an increase in human modified features like cropland (164 acres in 1989 to 303 acres in 2019 – 1.8 times increase) and built-up area (166 acres in 1989 to 284 acres in 2019 – 54.48% increase) and a subsequent decrease in natural areas such as wetlands, rivers and the floodplain over.

Regular monitoring of the spatio-temporal changes in the wetlands and their catchment area, and, assessing causal factors is necessary for developing robust conservation strategies for the restoration and management of these ecologically important ecosystems. As a significant outcome of the study, wetlands can be managed by integrating both landscape and biotic variables and can be classified into three groups – a. highly urbanised wetlands with high aquatic plant cover; b. wetlands with high agricultural pressure and low aquatic plant cover; c. wetland with low agricultural pressure and aquatic plant cover. Such a classification helps in making specific management recommendations and also in determining the prioritisation of conservation efforts to generate maximum impact.

Considering that majority of the decisions concerning management of urban greenspaces are made at the local level, and usually without the aid of scientific knowledge about their ecological effects, such study will help in making informed decisions for the management and conservation of wetlands along the Yamuna floodplains.

Footnote:

1http://watertales.wwfindia.org/about_wetlands.php

2https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/92813/urban-growth-of-new-delhi

3Khandekar, N. Delhi water bodies go under, almost. Published in Hindustan Times; February 3, 2011

Author: Ms. Subiksha Venkatesh R

Author is a postgraduate in Wildlife Sciences from the Amity Institute of Forestry and Wildlife, Amity University; Noida, Uttar Pradesh and is currently interning with Wetlands International South Asia.

Contact info: [email protected]