Securing wetlands for Sustainable WASH: A dialogue on Bhola Island, Bangladesh

-

Coastal resilience

-

Coastal wetland conservation

-

Integrating wetlands in water management

WASH interventions can be sustainable only when the sources of water and sinks of waste are secured and well managed. Can Bhola island afford to continue extracting deep water aquifers for meeting its water needs including that of WASH sector (water supply, sanitation and health)? Is rendering wetlands derelict and turning a blind eye, a sustainable pathway for the largest island of Bangladesh? In this Blog, Ritesh Sikka and Nehha Sharma reflect on the outcomes of a stakeholder workshop on IWRM-WASH integration held at Bhola Island, during 22-25 April 2019.

Situated at the mouth of Meghna River, Bhola is the largest island of Bangladesh spanning 3,403 km2 and inhabited by 1.7 million people. The island is formed in the estuarine floodplains of Meghna River. The distributaries of Meghna, Tentulia and Shahbazpur, separate Bhola from the mainland. The island is relatively young, believed to have emerged on the sediments of Ganga and Brahmaputra about 800 years ago.

Plentiful freshwater available in the northern and central part of the island provided the basis for agriculture. Wetlands provided an easy means of storing rainwater for domestic use. Post-1970s, with the introduction of borewell technologies, the possibility of increasing agriculture intensity through groundwater emerged, leading to a gradual reduction in dependence on wetlands as a single source of freshwater. As the technology to tap deep water aquifers became available soon-after, especially with the government agencies, it was possible to completely switch to groundwater to meet all freshwater needs. The productive wetlands turned into waste dumps. The depth at which water for drinking and domestic use is tapped is presently more than 1,000 feet.

Bangladesh has made significant strides in improving access to WASH services to its citizens. Open defecation had been reduced from 34% in 1990 to less than 1% of national population in 2015. Access to piped drinking water is nearly universal. The quality of sanitation, however, remains an area of concern, with an estimated 40% of toilets being unimproved. Similarly, over half of the drinking water sources fail to meet the water safety standards. One of the major limiting factors is progress in areas which present significant geographical and socioeconomic limitations, thereby resulting in low water and sanitation coverage. Island, wetland dominated landscapes as oxbows, marshlands and shallow depressions, and coasts have been observed to be such areas. As a means of better spatial targeting, such areas have been classed as hard to reach areas (a term assigned under a Water and Sanitation Programme research). Bhola island is one such area.

WASH interventions in Bhola have a focus on creating infrastructure and promoting behavioural change thus creating a demand for safe sanitation. Through relentless work of civil society, WASH has figured prominently in the local political agenda. Yet, the connection between water management and WASH, particularly the role of wetlands as a source of water and assimilator of waste is rarely recognised. With deep-water aquifers on a gradual decline, Bhola is progressing towards a water insecure future. The Watershed Bangladesh project aims to promote a sustainable approach to WASH including the sources and sinks on which WASH systems depend. The four-day workshop held under its aegis, during 22-25 April 2019 at Bhola island was focussed on sensitizing CSOs on interlinkages between water management and WASH and identify opportunities for community-led actions. Development Organisation of the Rural Poor (DORP) and Wetlands International South Asia were the workshop coorganizers. As many as 60 participants from local government departments, religious leaders, academics, and local communities attended the workshop.

Resource persons from Wetlands International and DORP opened the discussion by presenting the context in which WASH, wetlands and water management operated in a integrated. The participants voiced their concerns on the rapid degradation of Bhola Khal, a major canal running through the city. About 15 years back it was possible to navigate across the canal and was a star attraction for the tourist. It is no longer possible to do so as the canal is choked with silt, heavily encroached and is a dump yard of liquid and solid waste. Several instances of wetlands being filled in and encroached upon and their impacts such as the depletion of groundwater and in extreme cases erosion of the shoreline were mentioned.

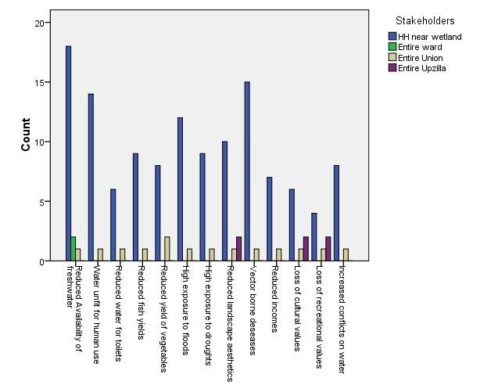

The outcomes of a detailed survey of 40 wetlands conducted by DORP during November-December 2018 were shared at the workshop. Data collected in the survey brings out the diverse role of wetlands in making the island, water and food secure, and the ways in which degradation of these ecosystems impacts various parts of the society. With multiple agencies involved, management of wetlands is complex, and no-one has the ultimate responsibility to conserve and sustainably manage these ecosystems. Even private pond owners expected the government to have the ultimate responsibility for maintenance and upkeep of the waterbodies. The need for a multilevel response involving individuals, community groups, Zila and Upzilla authorities was emphasized.

The deliberation and field visit made in four days led to three major outcomes. Firstly, the Union Chairmen agreed to include wetlands conservation as an action within the annual plan of the newly formed IWRM (Integrated Water Resource Management) committees. Secondly, The Deputy Commissioner sought a follow-up meeting to re-activate the IWRM committee at the district level so that coordination between different water users can be enhanced. Lastly, the local CSOs committed to share knowledge gained on importance of wetland management with the local communities, take practical actions to avoid misuse of groundwater and create awareness to reduce pollution of the wetlands.

The workshop has opened up opportunities for securing the role of wetlands towards enhancing water security of Bhola island. This is however just a beginning. Much needs to be done to ensure that wetlands are restored to a healthy state and that dependence on deepwater aquifers as a single source of freshwater is reduced. Building CSOs capacity is the key to this transition as they connect local communities with various levels of governance and can be harbingers of integrated thinking