Carbon Beneath Our Boots: A Field Journey through Uttarakhand’s Hidden Wetlands

-

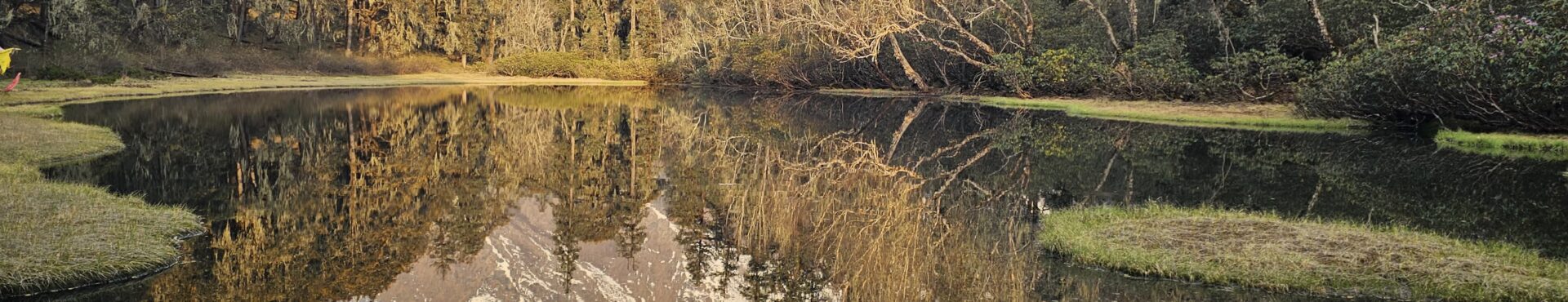

Healthy Wetland Nature

-

Peatland conservation and restoration

-

Peatland Treasures

-

Wetland values, status and trends

Into the Wild for Peat

Between April 24 and May 3, 2025, the three of us—Anil, Nikita and Arif—set out on a field expedition that turned out to be as humbling as it was enlightening. Our mission was clear: to trace, study, and sample peatlands in the higher reaches of Uttarakhand. But what we didn’t anticipate was how deeply the landscapes, people, and the sheer stillness of those wetlands would stay with us long after we returned.

Why Peatlands?

Often overlooked in conservation conversations, peatlands are nature’s quiet archivists. These waterlogged ecosystems slowly build up layers of partially decayed vegetation, locking carbon for centuries, sometimes even millennia. Globally, they hold more carbon than all the world’s forests combined, and yet, in India, we are only just beginning to uncover their secrets.

This trip was part of a broader effort to map, monitor, and better understand these ecosystems in India, especially in the context of carbon stock assessments and climate action.

Our Journey: From Forest Trails to Wetland Carbon Sinks

We conducted systematic fieldwork at each site to assess ecological conditions and carbon storage potential. We extracted peat soil for analysis using an auger, complemented by on-site pH testing and vegetation surveys. We also completed a standardised peatland assessment form, documenting wetland type, vegetation, water source, visible threats, and cultural significance. Beyond the data, we closely observed how water flowed, how moss formed mats, and how the landscape revealed its story—subtle signs that speak to the health and complexity of these ecosystems.

Reaching the high-altitude wetlands of Uttarkashi was no small task. We covered five distinct sampling locations across the district. One of our longest trails stretched over 28 kilometres, which we split across three days. On the first night, we camped deep in the forest, surrounded by the rustling of deodar and pine trees. The next day’s climb took us into a snow-laced silence, through a rhododendron patch that spread like a blush across the hillside. The final stretch—windy, snowy, and steep—tested our endurance but rewarded us richly. These wetlands offered more than scenic beauty: we heard the call of the Himalayan Monal, wild boar, watched Himalayan grey langurs leap through treetops, and caught the quiet gaze of a sambar doe with her fawns.

Another trek in the district led us to an open alpine meadow. At first glance, it seemed like just another grassy landscape—but the soil beneath told a deeper story. Dark, fibrous, and rich with carbon, it hinted at years of slow accumulation, reminding us that wetlands often hide their character below the surface. A Himalayan griffon soared above us as we sampled the site, scanning the terrain just as we did, in search of subtle signs.

Our fieldwork revealed how silently these wetlands store carbon—held tightly in their deep, dark soils. Still largely undisturbed, these sites continue to write their peatland stories, one quiet layer at a time.

In Dehradun district our work took us to a more managed wetland environment, shaped by human intervention and regulated water flow. This site, with its bustling birdlife and hydrological controls, provided a contrasting lens— of hydrological influence and habitat diversity.

Our final site in Haridwar offered a distinct and revealing perspective. Set in a more open and elevated part of the landscape, it reflected a different wetland dynamic—one shaped by its natural setting, seasonal rhythms, and sunlight. The site reminded us of the rich diversity within wetland systems, where each location expresses its own character depending on water, terrain, and ecological context. While sampling here, we were joined by herds of cheetal (spotted deer), and spotted a lone sambar deep within the reeds.

The People We Met

Throughout our journey, we were guided by local mule handlers, or khacchar walas, who not only guided us through the rugged terrain but also shared stories passed down through generations. They spoke of sacred lakes, silent zones, and the deep reverence mountain communities hold for these ecosystems. In their words, the landscape came alive, not just as a site for sampling, but as a place of worship and memory.

At the forest camp, we were welcomed with warm food, kind words, and a place to rest, small acts of hospitality that carried great warmth after long, cold days.

Towards the end of our fieldwork, we met with a government official in Dehradun. The discussion focused on how scientific findings like ours can support conservation at the policy level, especially the need to map and protect peatlands more effectively.

What Comes Next

This trip was just the beginning. Our samples are now undergoing lab analysis, and we’re compiling spatial data to build India’s peatland story—one that is currently hidden from national inventories and conservation plans.

The beauty of fieldwork lies not just in the data, but in what it reminds us: that ecosystems like these are living, breathing time capsules, holding carbon, biodiversity, and culture together. And they deserve to be known, protected, and passed on. Read More